Ghost Town 64

on Fri May 01 2020 by Ingo HinterdingOver the last year I disassembled the Commodore 16 game and ported it to the Commodore 64. This is my retrospective.

If you follow this blog or my twitter account @awsm9000, you know already that my obsession for this old game by Udo Gertz is almost unhealthy and worrying… But I had one more adventure to take on and I’ve finally completed this as well: a complete port of the Commodore 16 game to the Commodore 64, including many improvements.

This is quite a long article, covering all aspects of the conversion from dissassembling, coding, music, graphics to releasing the game. It may take a coffee or two to read, but I think it is a good read.

“Previously, on Ghost Town…”

It all started with a conversion of the game to JavaScript. I wanted to acquire more JS developer skills and looking for a project to take on this was a great experience. You can play the full game here: http://www.kingsoft.de/ghosttown/

I’ve written about the creation process in my previous blog, a summary of these posts can be read here: /blog/ghosttown-javascript/

Shortly after releasing the game I had a nice conversation with André Eymann from http://www.videospielgeschichten.de and as a result I wrote an article about my childhood experience with the game and the process of creating the faithful conversion for the browser. The text is written in german language only, you can read it either on https://www.videospielgeschichten.de/ghost-town-showdown-in-javascript/ or on my website at /blog/ghosttown-story/.

The Commodore 64 port

As mentioned before, there was one final barrier to break, which was completely disassembling the code to port the game over to other platforms. The Commodore 64 was my first choice, since I’m most familiar with that machine and the game had never been released for it, nor any other platform actually (although there was a predecessor of the game on Commodore VIC20).

Disassembly

Disassembling a game means that you take the binary file (which is just a sequence of numbers in hex notation like

A9 1B 8D 11 D0 A9 C8 8D 16 D0 A9 03 8D 00 DD 60

and convert it into Assembly code, which looks like this:

.C:419c A9 1B LDA #$1B

.C:419e 8D 11 D0 STA $D011

.C:41a1 A9 C8 LDA #$C8

.C:41a3 8D 16 D0 STA $FF07

.C:41a6 A9 03 LDA #$03

.C:41a8 8D 00 DD STA $DD00

.C:41ab 60 RTSLuckily, there are tools that help you with this, like Regenerator for Windows. Since I’m working on a Mac, I had to use a Windows Virtual Machine. Many great tools for C64 development are Windows-only, sadly. Converting the code back to a reusable state is still a complete pain in the butt though. While the compiler wouldn’t make any difference between code and data (like graphics, sound etc.), it’s crucial to identify the different sections of the game in order to make changes to them.

Also, more often than not the binary file is packed with crunchers like exomizer to reduce the file size when loading. Back in 1985 loading times, especially from the super slow datasette and 1541 floppy drive where a big deal. You have to make sure that the file is first unpacked and then you save the memory dump of the emulator.

The first milestone was getting the regenerated code to compile and run on the Commodore 16 again. With some help of my groupmate SpiderJ, who had done an excellent C16 to C64 port of Tutti Frutti previously, it wasn’t too difficult.

It was time to setup the project, which, in my case, means that I check the code into a github repository. If you haven’t worked with git before you might think that this is not needed for single developer projects, but once you get used to working with versioning tools, you’ll never want to miss them. Things can go wrong very easily when you refactor code and you might end up with a ton of “WTF!”s quickly. Having the option to set working milestones and go back to them in case something breaks inexplicably is a luxury you can’t miss out on.

I have made the finished project available on github so you can mess around with it yourself: https://github.com/Esshahn/Ghost-Town

My development environment is based on Visual Studio Code, which I use for regular development on a daily basis. It’s modern, lightweight, multi platform and free. I’ve created a github repository with step by step instructions on how to set everything up: https://github.com/Esshahn/acme-assembly-vscode-template. It’s the only solution I know currently that works for Windows, Mac and Linux, so give it a try.

Victory is relative

With the code compiling and running on the C16 we have achieved an important milestone (so go check it into git! It’s the modern version of Al Lowe‘s “Save early save often”). For the first time we now could change a value in the program, compile it and see the results, e.g. if we change the border color.

But as soon as we start adding or removing code, the game would fail to work or behave unpredictably. This is because the code is referencing absolute addresses, not relative. Here’s an example:

419C LDA #$1B ; we can easily change $1b to any other value

419E STA $D011

[ ... ] ; <- but we can't insert code here!

41A1 LDA #$C8

41A3 STA $FF07

41A6 LDA #$03

41A8 STA $DD00

41Ab JMP $41A1 ; because this jump address wouldn't be correct anymoreAs soon as we add or remove bytes from the file, absolute jump addresses would change and wrong code would be executed. This is a tough problem, as it can be super easy to accidentally change the byte count when making small changes. Replacing a STA $D020 (3 bytes: 8D 00 DD) with a RTS (1 byte: 60) would change the absolute addresses by 2 bytes.

The solution is simple: we use labels for relative jump addresses. The code above (which admittedly makes no sense at all) would read like this:

419C LDA #$1B

419E STA $D011

.l41A1

41A1 LDA #$C8

41A3 STA $FF07

41A6 LDA #$03

41A8 STA $DD00

41Ab JMP l41A1 The only change is that I added a label .lA1A1 at the position where the JMP command would jump to and changed the absolute address $41A1 to the relative label .la1A1. With that change we could insert a line of code in this little block without breaking the jump address! Sweeeet.

You might ask yourself why I used the absolute address as the label name and not something like .loop_start or more descriptive. Two reasons: At this point I might not have a clue what the code actually does, so I might make wrong assumptions. I could call the label init_sound_routine when in fact I learn at a later stage that this wasn’t what the code is doing. I will replace the labels with meaningful names, but it’s a task for a later stage. The second reason is that code might break a lot when you refactor it and you can easily spot an error when you debug the code and see that the label name and the absolute address mismatch.

But the game would still crash. Because even if this small part of the code was fixed, all the remaining absolute addresses would be affected by the shifted code. AAARGGH! So yes, we have to change every single absolute address in the code to a relative one. This is – by far – the most tedious and annoying task in the whole conversion process. Also it is quite error prone because of it’s repetitive yet complex nature. I divided the code into smaller chunks and converted these one by one over a period of several days. Be patient and don’t give up. If you make it through this phase everything gets easier.

Hint: Keep searching for mnemonic instructions that use addresses and go through them with your editor’s search and replace function. For example, look for JMP $ and replace every result with a labeled jump address. Other search queries could be LDA $, STA $, BNE $, BPL $, JSR $ and so on. You’ll find a complete list of opcodes here: http://6502.org/tutorials/6502opcodes.html

After a lot of work, the whole code is now cleaned of absolute addresses and should still compile and execute as expected.

Law Structure and Order

It is now time to understand the code and give it more structure. Until now, a monkey could be trained to do the job (and probably be better at it, too), but we want to have nice sections that we could save as separate files, e.g. the level data, the music, the charset and so on.

The file structure for Ghost Town 64

c64/

build/

labels

main.prg

code/

includes/

charset-extended.bin

charset.bin

intro.asm

items.asm

levels.asm

petscii-intro.asm

screen-win-en.scr

title-extended.scr

title.scr

main.asm

gfx/

[..]

music/

[..]While I structured the code and tried to understand and reproduce the behavior of the code I commented as much as possible, even the more trivial parts. I do this because writing down my thoughts helps me stay focussed.

This is a typical code segment from the game:

; ==============================================================================

; I moved this out of the main loop and call it once when changing rooms

; TODO: call it only when room 4 is entered

; ==============================================================================

room_04_prep_door:

lda current_room + 1 ; get current room

cmp #04 ; is it 4? (coffins)

bne ++ ; nope

lda #$03 ; OMG YES! How did you know?? (and get door char)

ldy m394A + 1

beq +

lda #$f6 ; put fake door char in place (making it closed)

+ sta SCREENRAM + $f9

++ rtsAs you can see I’m using anonymous foward (+) and backward (-) labels instead of named ones. This is good practice if we do not leave the function and are just looping or branching inside it.

Let’s do a recap where we stand

- the code is disassembled and can be compiled again

- all absolute addressing is replaced by relative addressing

- data chunks have been identified as either code or data (graphics, sounds, charset etc.)

- parts of the code have been moved into dedicated files

- the code is understood and commented

That’s the end of the hard part and a huge milestone (…save early, save often…). We now have the annotated source code of a 35 year old game. At this point we could make changes to any part of the game, like edit the levels, change the player character, or turn a deadly foot trap into a flower.

It’s our town now! HARR HARR HARR HARR

Changing the host

From this point on I’m working with two codebases: one for the Commodore 16 and one for the Commodore 64. It would be possible to use conditional expressions from your assembler (I’m using ACME) to distinguish between both machines when compiling the code, but it get’s messy and is in my opinion not worth the trouble.

The C16 game would obviously not run on the C64 without changes, so that is what we’re taking care of next. Converting a game from the C16 to the C64 is probably the most comfortable path, as the C16 has few features the C64 lacks. The main differences relevant to Ghost Town are

- 121 colors instead of just 16 (not so important for the game)

- 16k instead of 64k memory (which makes it easier)

- no sprites vs sprites (therefore we don’t need sprites at all)

- terrible TED music (which we need to take care of for sure)

I’m dealing with graphics and sound a bit later, let’s focus on the code first. To understand both machines better, we need to know how the memory and the functionality works. The Commodore 16 and 64 have memory mapped IO, which means that you can change a value in memory and immediately see the result.

Example:

POKE 65305,0: changes the border of the C16 to black

POKE 53280,0: changes the border of the C64 to blackSame for assembly code:

LDA #$00

STA $FF19 ; change border color to black on C16

LDA #$00

STA $D020 ; change border color to black on C64To make the conversion easier, I use labels again and replace the border color address $FF19 with BORDER_COLOR and give it a different value on the C64

BORDER_COLOR = $D020

LDA #$00

STA BORDER_COLORYou will need memory maps for both machines showing you the memory layout and how to convert addresses to match the target machine.

I’ve created a memory map (based on Zimmers.net) for the Commodore 64 here: https://mem64.awsm.de. A less comprehensive memory map for the Commodore 16 & Plus/4 can be found here.

I’ve used label definitions for the most common addresses, e.g.

TAPE_BUFFER = $033c ; $0333

SCREENRAM = $0400 ; $0C00 ; PLUS/4 default SCREEN

COLRAM = $d800 ; $0800 ; PLUS/4 COLOR RAM

PRINT_KERNAL = $ffd2 ; $c56b

BASIC_DA89 = $e8ea ; $da89 ; scroll screen up by 1 line

FF07 = $d016 ; $FF07 ; FF07 scroll & multicolorTo my surprise, very few changes had to be made to adapt the code to the C64. I was able to see first working bits of the game after changing the SCREEN and COLOR RAM througout the code, and when I removed the TED based music the title screen did come up already. Next up were the typical code blocks like joystick routines, IRQs, character display and screen settings and so on. It probably took me a day to get a first version to run. At this point you might wonder why the creator of the game, Udo Gertz, didn’t release a version for the C64 right away if it was so easy to port. My theory is that back in 1985 the code was written on the actual target machine and getting it cleaned and structured was a whole different story than with the tools we have today.

From TED to SID: the music

There are multiple ways to convert the music from the TED to the SID chip. Spoiler alert: none of them is good. To begin with, the original tune by Brigitte Gertz (information about her is shady at best, but Udo Gertz’s sister seems to be the composer of many tunes for his games) is, to say it polite and fitting the game’s theme: haunting.

Here’s an OGG version of the music, but be prepared and keep the volume of your speaker at a minimum: http://www.kingsoft.de/ghosttown/sound/ghost-town-loop.ogg

I know already from my JavaScript conversion that I do not posess the artistic skill to recreate the music in a SID compatible sound format myself. I tried. It was embarassing. All evidence has been destroyed.

Once again, SpiderJ to the rescue! He’s not only a great coder, but even more a very talented musician. It was a dangerous assignment, he could have easily died from swallowing his own vomit or turned deaf. But he came out on top, victorious, and delivered not one but three versions of the original tune. One was a close approximation to the original, one called “Industrial Town” a darker, heavy remix and one called “Meditation Town” is a bit more mellow. I decided to value SpiderJ’s creativity and go for the darker remix. Replacing the TED code with the SID routine was a matter of minutes. All three tunes can be found in the repository, including the *.sng files to edit them in GoatTracker: https://github.com/Esshahn/Ghost-Town/tree/master/extras/music-spider/psid64

Graphics

As for the graphics of Ghost Town, it was less about restrictions or differences and more about my urge to update them to an overall better look. It is up to you to decide if I succeeded. The game can be compiled with the old graphics as well if you want the truly authentic experience, but I didn’t include that option in the game itself.

Let me show you a screen from the C16 version:

I do like the level graphics, the rocks look okay, the plants are a bit blant maybe. But what the freck is wrong with the player character?! He has a ready-to-puke-shitloads-green face and pink hair! I do know that restrictions apply in color choices when working with character sets and multicolor mode, but the colors to make it right were already there! Why not make the face pink and the hair brown? For fuck’s sake, Udo. That was a trippy night when you implemented that character, right?

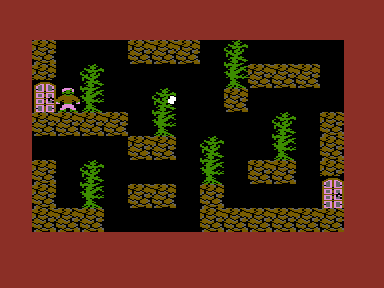

Here’s the C64 version of the same screen:

Switching around colors for the player character made a huge difference. It felt like fixing a bug, not making an artistic choice. I made more adjustments to the rest of the graphics. You can see that the plants got a separate stem color. The rocks look a bit less flat with slight dithering and an additional color which is not as similar as the brown (check the C16 image again… yes, there is a tone of grey in the original rocks, too). That white blob in the tree is supposed to be a glove, so I tried to make it more… glovey.

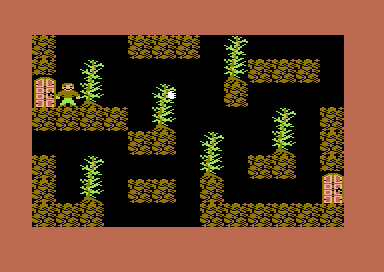

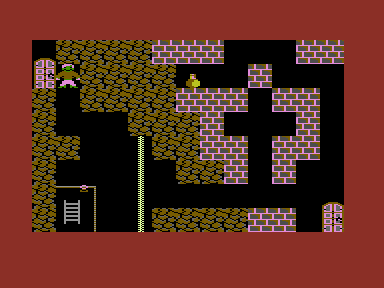

These little adjustments are made throughout the game. I did not change what I didn’t think needed fixing though and tried to stay truthful to the original. Here’s another screen from the original version:

And here with updated graphics:

You can see that I changed the brick wall. For once, it wasn’t looking good with the limited color variety of the C64, but I didn’t like that the bricks looked almost like inverted, with the mortar being lighter than the stone. Again it looked like colors had accidentally been swapped in the first place. I corrected that.

You might also notice that I slightly tweaked the ladder (why only use one color when we have the luxury of two colors) and the vase, which I think got significantly improved and is looking quite shiny now.

At this point it was clear to me that I did not only want to create a port for the Commodore 64, but also release an updated version of this game for the Commodore 16. Therefore I kept maintaining the two codebases, adding changes to both of them.

Fluffing it up

With the game now running on both platforms and music and graphics done for the C64, it was time to complete the package. As it goes with high ambitions, I had so much more in mind when I planned the port. First of all, I wanted to make use of the hardware sprites for additional effects, like moving clouds or little spiders running around, weeee! And I wanted to introduce sound effects. And while I was at it, a sprite based animated character would be cool! Stuff like that. It turned out I didn’t do any of it. Because I’m lazy, but also because I learned the hard way that there is indeed a “too much Ghost Town”. I even started to write a solution to the game in the form of a short story. It was heavy shit. And remarkably poor written.

Localization

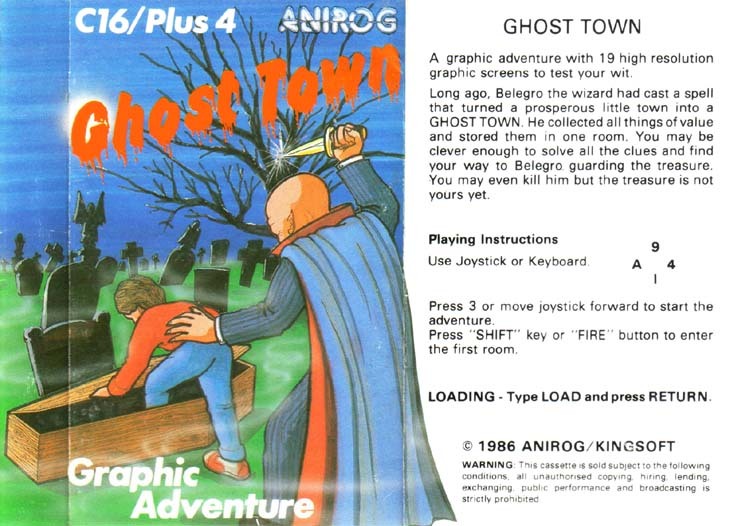

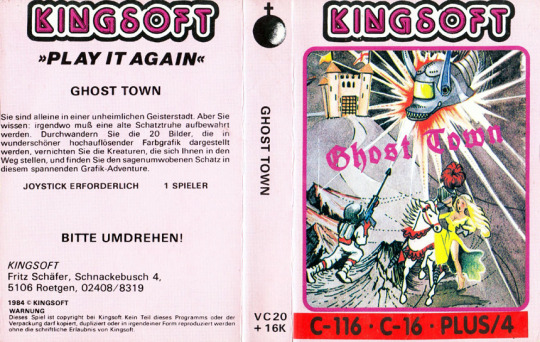

When the game was released in 1985 it came in two flavors: german and english. To my knowledge it has only been released on datasette either as a standalone game or as part of a compilation. Below you can see two different cover artworks. I have never seen the pink one in the wild and it does look like a reused packaging from the earlier released VC20 version. I’m still browsing eBay every now and then looking for it. If you own it and want to make me very happy, let me know… 😉

The Commodore 264 series was pretty popular in Hungary, too. At some point Commodore must have decided to dump all machines over there because they turned out to be commercial failures in the western regions. Because of that, there’s a lively and lovely 264 scene in Hungary. I wanted to pay that scene some respect and asked Károly Balogh (Charlie) if he could provide a translation. He did in a matter of hours so I was quite happy I could offer the game in hungarian language for the first time.

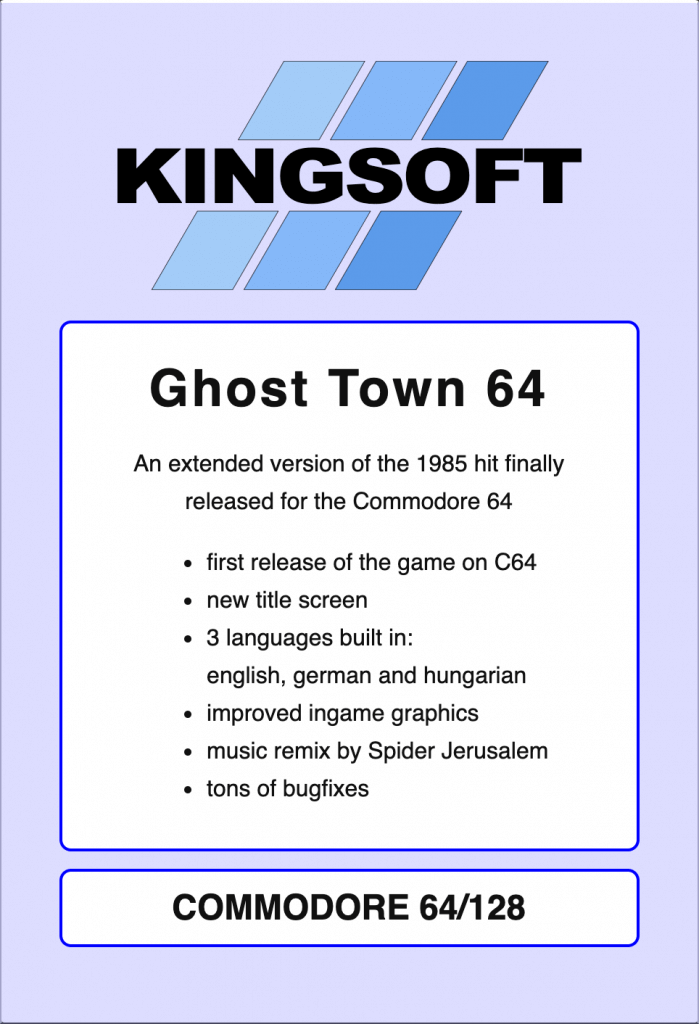

Since the C64 has 64k and Ghost Town is only using 16k of memory I had enough space to include all three languages in the game and let the player choose. To make it a bit more fun and atmospheric I created this PETSCII screen. The language can be selected with the joystick:

Multicolor Bitmap Title Screen

I quite liked the cheesy atmosphere of the datasette cover artwork and since the ingame title screen is pretty dull I decided to recreate that painting for both the C64 and C16 & Plus/4. I have some experience in pixeling these kind of graphics for the C64 so I didn’t worry too much about getting it right for the other platform. Boy was I wrong. It turned out to my surprise that with the benefit of a bigger color palette comes a huge restriction in how colors can be handled. I have already erased my memory about what exactly was different from how it works on the C64, but it was totally weird. Or, as somebody put it out:

Multicolor graphics for the 264 series is like having a child between an Amiga 500 and a Sinclair Spectrum.

Anyway, here are some workstages of the creation process. I’m mostly using Aseprite, the editor is perfect for pixel graphics, for example it has predefined color palettes and pixel doubling, which is essential for multicolor images which are 160×200 with double wide pixels.

I used the C16 color palette for most of the time and later converted the image to the C64 colors. After that I converted the C64 version again to the C16. Final touches are then done in Multipaint and from there I export the image to a PRG file and fetch my data from the emulator. I’m pretty pleased with the final result and I think despite their individual limitations both versions came out okay.

Almost done

With the language screen and the title graphics included and working, Ghost Town is now basically finished. I use exomizer to squeeze everythink together, it works flawless for both platforms.

It’s time to send the “release candidates” to friends for testing. The game needs to be tested for bugs, the localization has to be correct and of course it needs to run flawlessly on the real machines, not only in the emulator.

Website

In the meantime I create a small dedicated website to host the games on. They will be available on the scene websites csdb.dk (C64) and plus4world.com (C16 & Plus/4) as well, but I wanted more retro feeling. The original publisher of these games back in the day was called Kingsoft. Based in Germany, they focussed mainly on the 8 bit Commodore machines and supported the 264 series early on. Kingsoft went bankrupt in 1995 and all IP was transferred to Electronic Arts in the process.

I hope I’m not bringing any lawyers to ideas here when I say that I registered the domain http://www.kingsoft.de a while ago, go check it out. It hosted the JavaScript version of Ghost Town already and now I wanted to expand it to host all versions. At that time I was already a bit impatient as I really wanted to release the game, so I didn’t go nuts with the site and kept it quite basic. To display the games I chose a design resembling the typical style Kingsoft used for many releases, including almost all their books.

The test results are in

The testers went above and beyond, which was great. Stefan Vogt did some play sessions on real hardware and confirmed everything was working. Luca/Fire did not only test the builds, he also suggested some code fixes for PAL/NTSC compatability and he provided me code to convert the new SID remix by SpiderJ back to the C16 & Plus/4. Other testers helped out with last minute changes like typos or fixing a sound issue. A big thanks to all the testers.

Release with a sprinkle of drama, baby!

With all features in, green lights from the testers and the website ready and updated, the moment I had worked for had finally come: release time!

Man was I excited! Not that I expected the internet to go crazy, but it was a long trip and I was happy I finished the project. First I launched the updated website, then I gave some of the retro scene websites a quick notice that the game had launched (I had fun preparing a “media kit” in advance and make it available to them, just like how you do it when you release a real game).

Next up would be to upload the game on csdb.dk, the scener database. I was shocked to see that the game was already released there, cracked by Laxity. How on earth would they manage to release the game before me, the creator of the port? That was impossible! I was so puzzled that I contacted all testers and asked them if they had anything to do with it.

For those who are not familiar with the cracking scene, a short explanation. Back in the 80s almost all games were cracked, pirated and spread around for free. For every game bought legally there were ten pirated copies. The demo scene evolved out of the small intros crackers put in front of the games and the groups tried to beat each other both technically and artistically. It since has become a form of art. Most cracks also included trainer versions, which means that the player can have unlimited lifes or skip levels and so on. Ultimately, the cracked versions were often better than the retail games.

I expected cracked versions of the game, I was actually hoping for them to come up, it is part of the fun, much like a music remix where an artist takes your creation and adds new aspects to it. And since this was a free game there was no harm done anyway.

But the speed of the release was baffling. One tester called me and while swearing he wasn’t the culprit, supposed that somebody might have installed a keylogger on his computer and hacked it to get access to the game. Once we took off our tinfoil hats we had a good laugh. That alone was worth it!

It turned out, I myself was the snitch.

The other night, just before going to bed, I changed the game’s github repository from “private” to “public” in preparation to the upcoming release. I had a checklist of things I needed to do and figured that this would be a task I could do in advance as surely nobody would watch my account.

Well, Laxity did.

I can’t put it in any other way as to give them my respect for being this dedicated to the cracking scene. They must have followed my account, seen the newly added public repo and then spend the better half of their night to add their intro and some documentation. They actually beat me with my own release. Astonishing.

The game was very well received despite it’s unforgiving nature, with a very nice post by Luca on plus4world, a review on indieretronews or a great article by Paulo on Vintage Is The New Old who did a short interview with me. There’s even a really amazing review and playthrough on youtube by retro recollections. Thank you all for taking the time to review the game and spread the word.

The End…?

With the game released for the Commodore 64 and the C16 & Plus/4 with 64k my adventure with the Ghost Town has come to an end. I have approached it from so many angles, I wrote a story about it, I converted it to modern browsers and restored the source code to make the game available on a new platform. I feel my work is done, I can now board that last ship with the Elves and sail with them to wherever the fuck they went when they chickened out of battle when shit got crazy.

I would love to see other aspiring adventurers to grab the sword and continue the story. It would be so great to see more ports of the game. How about a version for Atari’s 8bit computers? With the lack of hardware specific features, Ghost Town would be an ideal candidate for a conversion. Or how about a sequel to the game with new graphics and puzzles? “Ghost Town 2: Belegro strikes back!”. Or a prequel: “Ghost Town 0: Belegro’s maze builder”. That would be so cool.

The source code is there, waiting for you.

Thank you for reading this article.

I hope you liked it.

Link summary:

- Download the game: http://www.kingsoft.de

- Github repository: https://github.com/Esshahn/Ghost-Town

- The VSCode + ACME assembler: https://github.com/Esshahn/acme-assembly-vscode-template

- Commodore 64 memory map: https://mem64.awsm.de

- Commodore 16 memory map: Link

- Developer Blog JavaScript version: /blog/ghosttown-javascript/

- My childhood memories with the game (in german): /blog/ghosttown-story/